Welcome to RADii+

Leaders in OTT and CTV Entertainment

powering content to a world-wide audience

Radii+ is Available on

NASCAR Fans Celebrate: A Free Streaming Channel Launches This Month

Fans' expectations for regular NASCAR TV content are coming reality. What was once merely hearsay is now a reality: NASCAR will have its own branded channel, free of charge. The NASCAR Channel will launch on the Tubi streaming network at the end of this month. The new...

Wildfire Relief Changes Will Be Implemented At The Grammys In 2025. Here Is What To Expect

The 2025 Grammy Awards are almost approaching, so it's time to start planning your viewing parties. Allow us to help. The 67th annual Grammy Awards will still be held on Sunday, February 2, at the Crypto.com Arena in Los Angeles, but the Recording Academy has shifted...

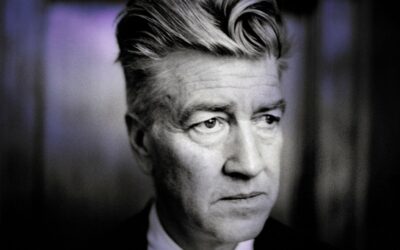

David Lynch, Director Of ‘Blue Velvet’ And ‘Twin Peaks’, Died At The Age Of 78

David Lynch, the famed "Twin Peaks" creator, has died, according to his family, who wrote on Facebook. The post reads: "It is with great sadness that we, his family, announce the death of the man and artist, David Lynch. We'd prefer some privacy at this time. There is...

U.S. TikTokers Come To Xiaohongshu, Confusing And Uniting With Chinese Users

"Hello, Chinese netizens! I am American; if you need assistance with your English assignments, please let me know!" Within a day, the 17-year-old had gotten approximately 2,000 responses. Rios is one of thousands of "TikTok refugees" who have rushed to Xiaohongshu...

Research: 66% Of US viewers Watch FAST Networks

According to Horowitz Research's most recent annual report, State of Media, Entertainment, and Tech: Viewing Behaviors 2024, two out of every three (66%) TV content watchers in the United States use free, ad-supported streaming TV (FAST) platforms on a monthly basis....

Now Drake Launches A Full-Fledged Defamation Case Against Universal Music Group

Earlier today, we learned that Drake has dropped a legal case against Universal Music Group and Spotify, accusing the businesses of conspiring to "artificially inflate" Kendrick Lamar's diss single Not Like Us. According to a legal document obtained by MBW today...

The Eagles Donated $2.5 Million For A FireAid Benefit Concert

The Eagles are setting the tone for the upcoming benefit concert for Los Angeles wildfire victims with a big first donation of more than seven figures. According to TMZ, the iconic rock band will make a $2.5 million donation. It's unclear whether the Eagles' large...

The Week Hollywood Stood Still: Entertainment Industry Struggles To Carry On Amidst Los Angeles Fire Devastation

On January 5, a renowned talent agent left a post-Golden Globes party early to catch up on work that had piled up over the holidays. Two days later, that mansion was destroyed by wildfires that ravaged Los Angeles' Pacific Palisades and Altadena neighborhoods, as well...

Matthew McConaughey And Woody Harrelson Star In A Texas Film Industry Advertisement

Texas-born Hollywood actors are banding together to promote the state's thriving film industry. Matthew McConaughey, Woody Harrelson, Dennis Quaid, Billy Bob Thornton, and Renée Zellweger recently appeared in an ad promoting the benefits of producing in Texas. This...

The Video Game Industry Is Finally Becoming Serious About Player Safety

In 2025, we will embark on a new era of safety by design for our digital playgrounds. Online games bring billions of people together to play, network, and unwind. However, they are also places where harassment, hate speech, and grooming for violence and sexual...

Eminem Destroys Suge Knight And Ja Rule In Leaked Diss Track “Smack You”

The song is more than two decades old. Eminem has moved on from the rap beef. He ended his 2024 song, "Guilty Conscience 2," by detailing all of his feuds over the years. He wants to put an end to fighting and instead focus on positive. The universe believed that fans...

Celebrities Including Arnold, Marshmello, And Sofia Have Contributed To A $100 Million GoFundMe Campaign For Fire Victims

People have donated nine figures to victims of the tragic Los Angeles wildfires thanks to online crowdsourcing, including some of Hollywood's biggest celebrities. TMZ has learned that GoFundMe has raised more than $100 million to directly assist families, towns, and...