Every time you open a website or app, a flurry of undetectable operations happens without your knowledge. Numerous advertising agencies are vying for your attention behind the scenes because they want to get their commercials in front of your eyes.

Which ads you view are frequently chosen through a series of rapid auctions for each ad. With $418 billion spent on it in 2017, automated advertising, sometimes referred to as programmatic advertising, is a significant industry. But abuse potential exists as well.

Today, security researchers exposed a fresh, pervasive attack on the online advertising ecosystem that affected millions of users, tricked hundreds of businesses, and may have even brought its developers some sizable revenues. Researchers at Human Security, a company that specializes in fraud and bot activity, found the threat, known as Vastflux. 11 million phones were affected by the hack, which involved the spoofing of 1,700 apps and the targeting of 120 publications. The attackers were sending 12 billion requests for advertisements daily at their height.

According to Marion Habiby, a data scientist at Human Security and the case’s primary researcher, “I had to run the statistics numerous times when I first got the findings for the volume of the attack.” The attack was one of the largest and most sophisticated the organization has ever experienced, according to Habiby. It is obvious that the bad actors were well-organized and took great care to avoid being discovered in order to ensure that the attack would last as long as possible—and earn as much money as possible, according to Habiby.

Online and mobile advertising is a complicated and frequently hazy industry. However, it makes a ton of money for those engaged. Every day, billions of advertisements are put on websites and in applications. Advertisers or ad networks pay to have their advertisements displayed and profit when users click on or otherwise interact with them.

In the summer of 2022, while looking into another issue, Human Security researcher Vikas Parthasarathy discovered Vastflux for the first time. According to Habiby, executing the scam required a number of steps, and the perpetrators used a variety of defenses to avoid being discovered.

First, the attackers would target well-known apps and attempt to purchase an advertising space within them. Human Security hasn’t released their name as a result of continuing investigations. “They were basically running through one ad spot,” Habiby claims. “They weren’t trying to hijack a complete phone, or an entire app.”

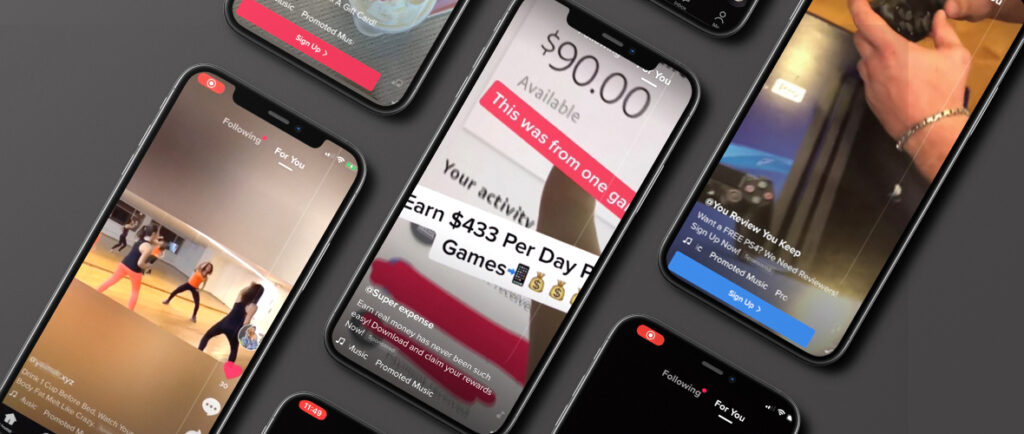

Once Vastflux won the bid for an ad, the organization would secretly add some harmful JavaScript code to that ad to permit the stacking of several video adverts.

Simply put, the attackers were able to take over the advertising system so that anytime a phone displayed an ad within a compromised app, up to 25 adverts would really be stacked on top of one another. You would only see one ad on your phone, and the attackers would be paid for each one. However, as it processed all the fake adverts, your phone’s battery would discharge more quickly than usual.

It’s extremely clever, says Habiby, because your attack ends the moment the ad vanishes, making it difficult to locate you.

The scope of this was enormous: in June 2022, the group’s busiest month, it was making 12 billion ad requests day. Although Android phones were also affected, according to Human Security, iOS devices were the main targets of the attack. On the whole, 11 million devices are thought to have been implicated in the fraud. Since legitimate apps and advertising systems were affected, there was little that device owners could have done to prevent the attack.

According to Google spokesman Michael Aciman, there was only a small amount of Vastflux “exposed” on the company’s networks due to strong restrictions against “invalid traffic.” “Our staff took quick enforcement action after carefully evaluating the report’s contents,” says Aciman. The request for response from WIRED was not answered by Apple.

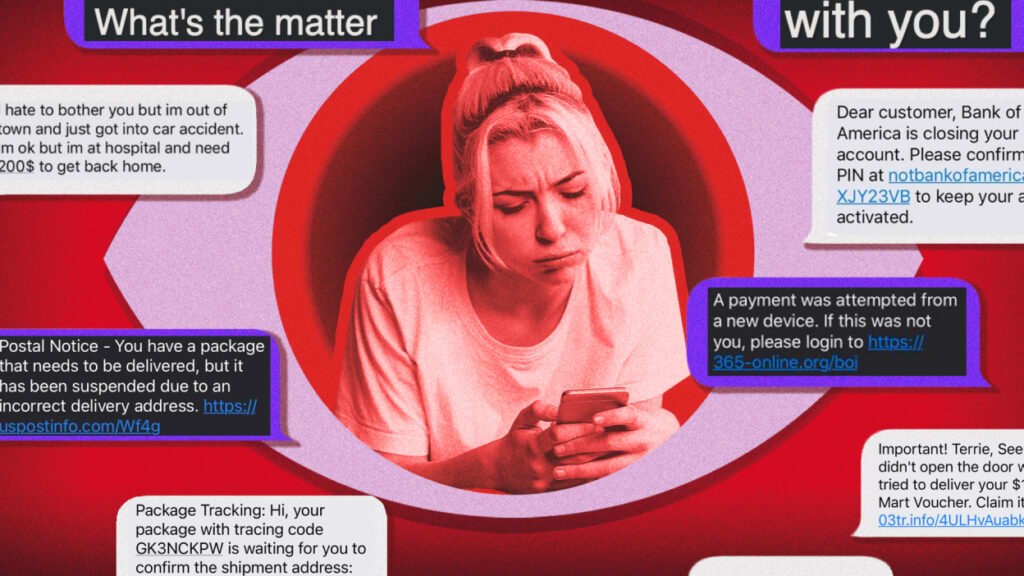

The varieties of mobile ad fraud might vary greatly. Similar to Vastflux, this can involve various forms of ad stacking, phone farms, click farms, and SDK spoofing. For phone users, swiftly depleting batteries, sharp increases in data usage, or screens going on erratically could be indicators that their device is being affected by ad fraud. Eight men were accused of conducting two well-known ad fraud schemes in November 2018 as part of the FBI’s largest ad fraud investigation. (The inquiry was supported by Human Security and other IT firms.) And in 2020, Uber was successful in an ad fraud lawsuit after a business it contracted to encourage more users to download its app engaged in “click flooding.”

In the case of Vastflux, it’s possible that those working in the enormous advertising sector itself were the ones who were most negatively affected by the attack. Both advertising agencies and apps that display adverts were impacted by the theft. According to Zach Edwards, senior manager of threat analytics at Human Security, “they were trying to defraud all these different groups throughout the supply chain, with different strategies against very diverse ones.”

The group employed several strategies to avoid being discovered because up to 25 consecutive ad requests from one phone would appear suspicious. They faked the advertising information for 1,700 apps, giving the impression that several separate apps were engaged in displaying the adverts when in reality only one was. In order to escape discovery, Vastflux adjusted its advertising so that only specific tags could be applied to them.

Attackers in the space are getting more sophisticated, according to Matthew Katz, head of marketplace quality at FreeWheel, a Comcast-owned ad tech company that was partially involved in the probe. Vastflux was a particularly intricate concept, according to Katz.

The researchers claim that the attack required extensive planning and infrastructure. According to Edwards, Vastflux launched its attack using a number of domains. Vastflux is a combination of the terms “rapid flux” (a technique hackers use to link several IP addresses to a single domain name) and VAST (a video advertising template created by a working group inside the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB), which was misused in the attack).

(Shailley Singh, executive vice president, product and chief operating officer at IAB Tech Lab, claims that using the VAST 4 version of its template can assist in preventing attacks like Vastflux, and that other technical measures from publishers and ad networks would assist in lessening its effectiveness.) It’s not the straightforward fraud technique that we frequently encounter, according to Habiby.

Invoking ongoing investigations, the researchers declined to say who might be responsible for the Vastflux or how much money they might have made. However, they assert that they have observed the same crooks engaging in advertising fraud as early as 2020. In that case, the ad fraud scheme allegedly collected user data while focusing on US swing states.

Vastflux has been halted for the time being, at least. Human Security and numerous businesses it has collaborated with to prevent ad fraud started actively battling the gang and the attack in June of last year. In June and July 2022, Vastflux was affected in three different ways, resulting in a reduction in the attack’s daily ad request volume to under a billion. In a blog post, the business claimed, “We discovered the unscrupulous actors behind the operation and worked closely with abused companies to limit the fraud.”

The perpetrators of the hack shut down the servers in December, and Human Security hasn’t noticed any activity from them since. There are a variety of activities consumers can take to stop criminal activity, some of which may result in law enforcement action, according to Tamer Hassan, the company’s CEO. However, cash is important. Attacks can be decreased by preventing perpetrators from making money. According to Hassan, “We win as an industry against cybercriminals by winning the economic game.”

Download The Radiant App To Start Watching!

Web: Watch Now

LGTV™: Download

ROKU™: Download

XBox™: Download

Samsung TV™: Download

Amazon Fire TV™: Download

Android TV™: Download