It’s an odd turn of events that a white hillbilly fiddler named Jim Stewart founded the greatest, funkiest soul label in the world, one of the most influential platforms for Black expression.

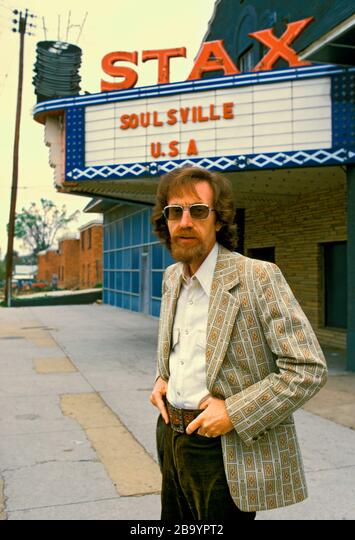

Stewart, a co-founder of Stax Records in Memphis, passed away on Monday at the age of 92. Stax Museum of American Soul Music acknowledged his loss in a statement, saying that he passed away “peacefully, surrounded by his family.”

Jim Stewart was at the center of it all as a producer, engineer, businessman, and mentor, according to the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame, which enshrined him in 2002.

Stewart’s generosity of spirit and desire to open doors, especially to young Black musicians, had a profound impact on those who knew and worked with him at Stax. If not for what Jim did and for who he was, Stax Records would not have existed, and soul music would not have been what it was, according to David Porter, a Hall of Fame songwriter for the label.

“Jim will always be admired for giving me and so many others the chance to do what we achieved. No matter how good we were, if Jim hadn’t been willing to open that door to his studio, record label, and heart, our music would not have existed. Jim was a catalyst, and he was a true pioneer, who is now gone.

The mild-mannered Stewart, a banker by profession, was an unexpected R&B and soul music fan, yet he would build a racially diverse record label in the 1960s segregated South, influencing some of the most important pieces of American music.

“Mr. I first met Stewart in 1962. He was a modest, soft-spoken white man with a Brylcreem-lathered hair part and heavy fat-rimmed spectacles, Deanie Parker, a former Stax publicist who later became head of the Soulsville Foundation, remembered. “He provided us with opportunities that were unavailable to the majority of Black Americans, and we gave him the irreplaceable Memphis sound that we jointly developed at Stax Records.

“Real, everlasting Memphis music is ageless authentic art that teaches and touches your soul like those legendary (sounds) recorded from 1957 to 1975 on the record label Jim Stewart formed,” continued Parker. “The best part of our amiable city is the music generated in the heart of South Memphis.”

From banking to releasing records

Stewart was raised in a musical family and played gospel music with his sisters, father, and uncle. He was born on July 29, 1930, in Middleton, Tennessee, a small town 70 miles east of Memphis. Stewart began playing the fiddle as a child and is a devotee of Western swing bandleader Bob Wills. “At my core, I’m a hillbilly. I grew up listening to the Grand Ole Opry,” Stewart stated in 2018 at the Stax Museum during a rare public visit.

Stewart relocated to Memphis after receiving his high school diploma, started working as a stock clerk, and then finished his military service, during which he performed fiddle in the special services. He started working in the bonds department at First National Bank after graduating from Memphis State University with a degree in business. Along with his law studies, Stewart participated in Canyon Cowboys on the weekends, where he played fiddle.

By 1957, independent record studios and labels, led by Sam Phillips’ Sun Records, had proliferated in Memphis. Stewart started to grasp the potential of making records. Stewart admitted his shortcomings to the writer Robert Gordon. “Producing was the greatest alternative because I knew I couldn’t succeed as a musician. It served as a platform for my musical expression.

After having a few of his songs rejected by Sun and other local and regional companies, Stewart would finally start his own label, Satellite, in 1957. Early on, Stewart teamed up with aspiring producer Lincoln “Chips” Moman, a rockabilly guitarist, and they started recording music, first in Stewart’s garage and later at a small studio in Brunswick, Tennessee.

They were able to purchase a new Ampex tape recorder and start producing albums thanks to the financial assistance of his sister, fellow bank employee Estelle Axton (the business would eventually alter its name to Stax – a combination of Stewart’s and Axton’s last names).

When Stewart made a 2018 presentation at the Stax Museum, he complimented his sister for taking the biggest risk possible to establish the label. She should receive full credit for Stax Records. She mortgaged her home to pay back loans she took out so we could launch a record label,” he claimed. “This would not have happened without that.”

Stax an anomaly in segregated South

The fledgling Satellite label would find a new and permanent home in South Memphis in 1959, at the former Capitol Theater at McLemore and College. The move, which took place in an increasingly Black neighborhood and was largely orchestrated by the R&B-inclined Moman, would alter the course of the company and Stewart’s life.

Satellite had been unsuccessfully cutting country and pop songs for nearly three years at this point. With money and opportunities running out, Stewart jumped at the chance to record an R&B duet, “Cause I Love You,” with veteran Memphis singer, entertainer, and DJ Rufus Thomas, who’d dropped by the studio with his 16-year-old daughter, Carla.

“Cause I Love You” became a regional hit within a few months of its release, selling thousands of copies in Memphis, Nashville, and Atlanta. Its success piqued the interest of Atlantic Records in New York, and company executive Jerry Wexler, who established a distribution relationship with Satellite.

Moreover, the success of “Cause I Love You” taught Stewart the value of R&B and provided him with the opportunity to make that music the focus of his label. Stewart told Stax historian Rob Bowman, “Prior to that, I had no idea what Black music was about.” “It was as if a blind man suddenly gained sight.”

Carla Thomas’ hit “Gee Whiz,” which sold half a million copies, and Rufus Thomas’ “Walking the Dog” would also chart, and Stax Records (as Satellite was officially renamed in 1961) was off and running. Other chart hits would soon follow, including the Mar-Keys’ “Last Night” and Booker T. and the MGs’ “Stay With Me.” “Green Onions” by & the MG’s, as well as the arrival of Georgia singer Otis Redding.

Stax would primarily use the talents of a core of young Black neighborhood kids from South Memphis to make its records over the next few years, including Booker T. Jones, William Bell, David Porter, and Isaac Hayes. As Stewart produced and guided the label through its early years, it was this remarkable group of artists who came to define the Stax sound (following the departure of Moman in 1962).

Even though Stax’s hits were iconic, the company’s environment—one in which Black and white employees created music side by side—was unusual in the segregated South of the 1960s. Outside of his label, Stewart continued to be acutely conscious of the injustices of the day. He told the tale of taking Carla Thomas, the breakthrough star of the Stax, to meet with Atlantic vice president Jerry Wexler in 2018.

Stewart remarked, “We couldn’t go to a restaurant in this city and have dinner together, even though Carla had a hit that was in the top 10 nationwide. “We had to take the freight elevator upstairs at the Claridge Hotel, where Wexler was staying. One of the worst feelings I’ve ever experienced was that. This young woman was a (star), but she was unable to pass through the Claridge Hotel’s lobby. It was one of those experiences in life that you would prefer to forget. But I’ll always remember that.

Al Bell: At Stax ‘you had harmony’

With the success of Carla Thomas, Sam & Dave, and Booker T, Stax would continue to prosper into the middle of the 1960s. & the MG’s and Redding’s ascension, one of its brightest stars.

Al Bell, a young Black disc jockey from Arkansas, was hired by Stewart in 1965 to oversee the label’s promotions. Bell and Stewart originally connected at Memphis radio station WLOK in the late 1950s. Bell and Stewart had an uncommon bond because they worked together in the same office at Stax.

“I was astounded to be sitting in the same room as this white guy who had been a country fiddle player,” Bell told author Robert Gordon. “In Memphis and throughout the South, we had separate water fountains.” And if we wanted to go to a restaurant, we had to go through the back door — but sitting in that office with this white man, sharing the same phone, sharing the same thoughts, and being treated as equal human beings was truly a phenomenon at the time.”

“Jim and Estelle Axton’s spirit allowed all of us, black and white, to come off the streets, where there was segregation and a negative attitude, and into the doors of Stax, where there was freedom, harmony, and people working together.” It grew into something that was truly an oasis for all of us.”

Stax would suffer a series of unexpected blows in the late 1960s, following a run of chart hits: Redding’s death in a 1967 plane crash, the company’s break with distribution partner Atlantic in 1968, and the pall cast over Memphis following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. that spring.

Stewart and his new partner, Al Bell, would relaunch Stax with the backing of entertainment conglomerate Gulf & Western after splitting with his sister Estelle Axton in 1968. Despite the fact that Stax had lost its entire back catalog due to a contractual snafu with Atlantic, the label launched its second phase with a “Soul Explosion,” releasing 27 new albums at once and reviving the label’s fortunes.

Celebrating Jim Stewart’s legacy

By the early 1970s, Stax had established itself as an entertainment powerhouse. The company was expanding its business in all directions, while also moving toward a greater sense of Black awareness and empowerment, as evidenced by events such as the massive WattStax concert and Isaac Hayes’ Oscar-winning soundtrack to the Blaxploitation hit “Shaft.”

Al Bell would eventually take over the company, buying out Stewart with the help of CBS Records. Despite Stax’s success, by 1974, a slew of forces had descended on the label, including the company’s creditors and the IRS. Stax found itself in dire financial straits and on the verge of bankruptcy in 1975.

Stewart had become wealthy, but when Stax ran into financial difficulties, he poured much of his fortune back into the company. Stewart lost nearly everything when Stax was finally swallowed up by creditors and closed down in 1976. He was forced to sell his possessions at auction in 1981 after the IRS seized his home and evicted him and his family.

Stewart was able to rebuild his life financially thanks to some holdings in his wife’s name, and he eventually returned to recording in the early ’80s, producing projects for several veteran Stax artists. Stewart, on the other hand, gradually distanced himself from the music industry and the public eye in later years.

Stewart has kept a low profile over the last 20 years, occasionally visiting the Stax Museum of American Soul Music, which opened in 2003 on the site of the original studio. Stewart was particularly proud of the work of the Stax Music Academy, which nurtured the talents of young Memphis musicians in the same way that the label had done decades before.

Stewart did make an emotional public return to the Stax Museum in 2018 as part of a legacy celebration, where his original fiddle was donated to the museum’s permanent collection.

A microphone was passed around the room during that event to allow the Stax alumni in attendance to introduce themselves. Carla Thomas, the Queen of Stax, spoke to Stewart. “Any crown that anybody says Stax Records wears, well, you’re a jewel in their crown,” Thomas said. “I adore you.”

Al Bell delivered the evening’s benediction, summarizing the affection for Stewart and his role in history.

“We all became a part of your dreams and visions… and we thank you for that, Jim Stewart,” a tearful Bell said. “Our lives would not have been the same if you hadn’t come along at the right time.” Thank you very much, and God bless you.”

Stewart appeared moved by the outpouring of love from so many old friends after the ceremony. “I’m speechless,” Stewart said softly, overcome by the outpouring of love.

Stewart leaves behind three children, Lori Stewart, Shannon Stewart, and Jeff Stewart, as well as grandchildren Alyssa Luibel and Jennifer Stewart. A memorial service is being planned.

In lieu of flowers, the family requests that memorial contributions be made to Stax Music Academy.

Download The Radiant App To Start Watching!

Web: Watch Now

LGTV™: Download

ROKU™: Download

XBox™: Download

Samsung TV™: Download

Amazon Fire TV™: Download

Android TV™: Download