The oldest DNA pieces have been found by scientists in the permafrost on Greenland’s northern border, providing an unusual window into an exceptional ancient ecosystem.

The genetic material is at least two million years old, which is nearly twice as old as the previous record-holder, the mammoth DNA found in Siberia. And more than 135 different species were represented in the samples, which were detailed in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

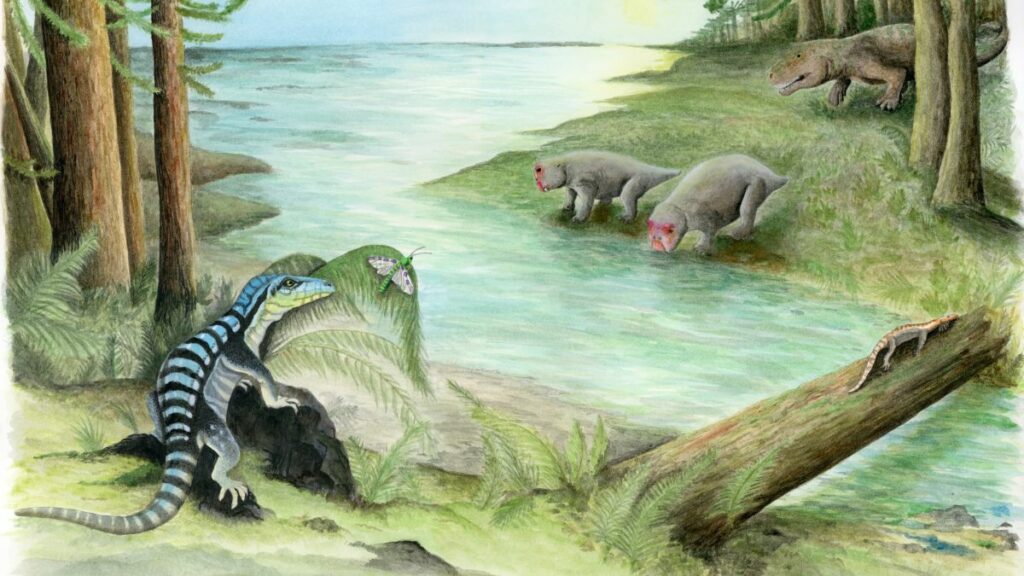

Together, they demonstrate how a region only 600 miles from the North Pole was formerly home to a mastodon-inhabited forest of poplar and birch trees. Caribou and Arctic hares could also be found in the forests. Horseshoe crabs, a species that is no longer seen north of Maine, were abundant in the warm coastal waters.

The study was praised as a significant advancement by other experts.

Beth Shapiro, a paleogeneticist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, remarked, “It feels almost magical to be able to deduce such a detailed picture of an ancient environment from microscopic bits of preserved DNA.”

Geoscientist Andrew Christ, who specializes in the ancient Arctic and works at the University of Vermont, predicted that the discovery would “blow people’s minds.” It undoubtedly did so for me.

After two decades of painful failures and scientific betrayals, the breakthrough was made.

As a graduate student at the University of Copenhagen, Eske Willerslev, one of the project’s directors, invented techniques for extracting DNA from silt. He and his colleagues discovered DNA from plants such as willow and daisies dating to 400,000 years ago in 2003 while examining a section of Siberian permafrost.

The fact that it was discovered broke the previous record for the oldest DNA, and many scientists questioned whether anything any older could be found. However, in northern Greenland in 2006, Dr. Willerslev and Kurt Kjaer, a geoscientist at the University of Copenhagen, attempted to defy the odds. They traveled to a group of barren hills known as Kap Kobenhavn, which was a geological structure as forlorn as the moon. There, 2.4 million-year-old plant fossils have previously been discovered by scientists. It would have been incredible to find DNA in the sediments.

Dr. Kjaer advised taking some risks if you wanted to advance the situation.

Permafrost was excavated, and the scientists brought it back to Copenhagen to look for DNA. They couldn’t locate any.

When Dr. Willerslev and his associates then looked at younger sediments and bones from other parts of the planet, they had more success. They made a significant amount of ancient human DNA discoveries that have altered how we think about the evolution of our species.

Along the way, the scientists improved the equipment they used to sequence the DNA and adjusted their techniques for removing it from ancient samples. They would pull out more of the Kap Kobenhavn samples as they got more adept at searching for genes.

However, they have consistently failed for years. They were occasionally teased by readings, which are what appeared to be brief DNA fragments. The chance that the readings were tainted by immature DNA fragments from Greenland or even their lab could not be completely ruled out by the researchers.

In 2017, they at last discovered DNA in the samples thanks to a significant advancement in technology. Genetic material was found to be abundant in the permafrost. They quickly gathered millions of DNA fragments.

It was a breakthrough, according to Dr. Willerslev. It changed from being nothing or very little that you weren’t sure was real to being there all of a sudden.

To determine where the fragments belonged on the evolutionary tree, the researchers linked up the fragments with DNA sequences of existing species. They discovered 102 distinct plant species, including 78 that were known from fossils and 24 new ones. Poplar and birch trees predominated in woodlands, according to the plant DNA.

It exceeded all of our expectations, according to Dr. Kjaer.

In addition, the researchers looked for fresh hints about the age of the fossils in the permafrost. The minerals in the layers of silt they discovered showed that the Earth’s magnetic field had flipped. The researchers were able to estimate Kap Kobenhavn’s age to be at least two million years old because to the age of those reversals, but they were unable to set a firm upper limit. As a geoscientist, “I have a gut feeling it’s older,” Dr. Kjaer added.

The notion that the DNA originated from more recent species and was introduced into the older permafrost was ruled out by the researchers. The absence of many of the mutations present in the DNA of current species in the Kap Kobenhavn birch trees suggests that they were ancient. Additionally, the DNA from Kap Kobenhavn had a specific pattern of damage that can only be seen when molecules have been buried in silt for protracted periods of geological time.

Tyler Murchie, a postdoctoral researcher at McMaster University who was not involved in the current work, said that it “truly helps prove that this actually is old DNA.”

Some of the species the researchers discovered caught them off guard. Today, caribou still exist throughout Greenland and a large portion of the Arctic. Their fossil record, however, revealed that they evolved a million years ago. Their DNA now has two times as much evolutionary history.

Love Dalén, a paleogeneticist from Stockholm University who last year found 1.2 million-year-old mammoth DNA in Siberia, was astounded to find mastodon remains in Greenland. He enquired, “What the hell are they doing up there?”

The closest known mastodon fossils, according to Dr. Dalén, are 75,000 years old and can be found in Nova Scotia. These bones are far more recent than the Greenland DNA and much farther south than Kap Kobenhavn. On dry land, “you can’t get any further north,” he remarked.

The Danish scientists came to the conclusion that the mastodons that lived in Greenland two million years ago belonged to a remote and previously undiscovered branch of the mastodon family tree. They might be the descendants of the known late-Pleistocene mastodons, or they might be a different species, according to Dr. Dalén.

Mastodons, as they did in North American forests, would thrive in a poplar-birch forest in Greenland. Despite the fact that caribou are most frequently seen in northern tundras, a subspecies inhabits Canadian woodlands, providing information about how the ancient caribou may have survived. Horseshoe crabs, however, are found in the shallow coastal waters, which indicates that both the ocean and the land were very warm.

Dr. Willerslev and his associates are still examining the DNA to look for hints as to how all of these species managed to survive 1,000 miles north of the Arctic Circle. For instance, the trees had to endure the dark for half the year. Their secrets of adaptation may be hidden in DNA that has been maintained for two million years.

The scientists are particularly curious about how the DNA pieces defied expectations by surviving for such a long time. According to their research, the DNA molecules can adhere to clay and feldspar minerals, shielding them from further harm.

On the basis of that finding, the researchers are creating new techniques in the hopes that they will enable them to extract even more DNA from prehistoric sediments. In an effort to beat their previous record, Dr. Kjaer and his associates are scouting sites in Canada that date back four million years.

They might succeed, according to Dr. Dalén. However, he believes it will be hard to identify ancient genetic material older than roughly five million years due to the damage that both he and the Danish researchers are seeing in the oldest DNA. He clarified, “This in no way implies that any DNA will come out of dinosaur-aged remains.

The discovery of more DNA from locations like Kap Kobenhavn, according to Dr. Christ, could benefit in the study of how human-induced climate change will affect the Arctic. He cautioned against assuming that the region’s ecosystems will be similar to those found further south. After all, there is no modern-day equivalent to the environment of Kap Kobenhavn two million years ago.

Dr. Christ stated that “life will adapt, but in ways we don’t expect.”

Download The Radiant App To Start Watching!

Web: Watch Now

LGTV™: Download

ROKU™: Download

XBox™: Download

Samsung TV™: Download

Amazon Fire TV™: Download

Android TV™: Download