According to a representative, YouTube’s Music and Premium services now have more than 80 million paying members combined, up a huge 30 million from the 50 million the firm disclosed in September of last year. This growth spurt has been astonishingly quick.

It’s a significant jump, especially for a platform where so much is available for free, and would seem to place YouTube, which already ranks as the top global music streaming service, as the third or fourth-largest paid music-streaming service in the world, behind Spotify, Apple Music, and China-only Tencent, although such rankings are always dotted with asterisks (such as whether or not free trials are included in the tally; YouTube includes them, which not all services do).

However, the development is impressive by any standard and coincides with an ongoing charm assault against artists and the music business.

After a few false starts, YouTube Music and Premium launched their subscription services in earnest in 2018, about 18 months after music chief Lyor Cohen joined the company. Cohen had previously held C-suite positions at Def Jam Records, Warner Music, and 300 Entertainment (which he co-founded and sold to Warner for an estimated $400 million in 2017). After years of tense interactions between YouTube and the music business over its relatively low royalty charges, that decision was made. Cohen’s occasionally infamously hostile temperament did not make things any better.

However, YouTube has now made a concerted effort to “partner” with the music industry. The corporation currently claims to have paid inventors, artists, and media companies more than $50 billion over the last three years. Included in this total is more than $6 billion given to the music industry between July 2021 and June 2022. Along with a bewildering array of other features to aid creators and labels in promoting their music, it has also stepped up its “twin-engine” revenue model (advertising and subscriptions). This includes YouTube Shorts, essentially its response to TikTok, which the company claims are now averaging 30 billion daily views.

However, $6 billion in a year says volumes. The chairman of Universal, the biggest music firm in the world, Lucian Grainge, remarked at the Music Matters conference in September, “It’s quite a sea change from where we were ten years ago,” yet top sources at music corporations say there is still a considerable value disparity on royalties. We make money, they make money, as Robert Kyncl, the former chief business officer of YouTube, said to Bloomberg last year. Kyncl will take over as CEO of Warner Music on January 1. Both of us and they succeed. Everything is perfectly aligned.

Cohen claims that there were numerous misconceptions on both sides. “So I started working gently, moving back and forth between engineers and the music business so they could hear one another.

He says, “We also didn’t have a team that [interfaced] with the labels. “Before I arrived, we were just a negotiation function that came around every three years to collect a signature, rather than working side by side with the industry to understand what’s essential to them. Like a result, we transitioned from being merely transactional to acting as a partner would. We also got to work explaining how subscriptions and advertising have grown in tandem; many record labels have invested much in subscription but not advertising.

He adds that “the [paid] subscription business” is the quick fix for the improvement. They believed we weren’t good partners because we didn’t have one and weren’t converting our funnel. And I believe that one of the reasons the corporate community is beginning to feel good about us is because of the success of our subscription business. (He also clarified the term “free” for YouTube’s ad-supported alternative, saying, “I usually push back on calling it free – it’s not free.”) They compensate with their eyes.)

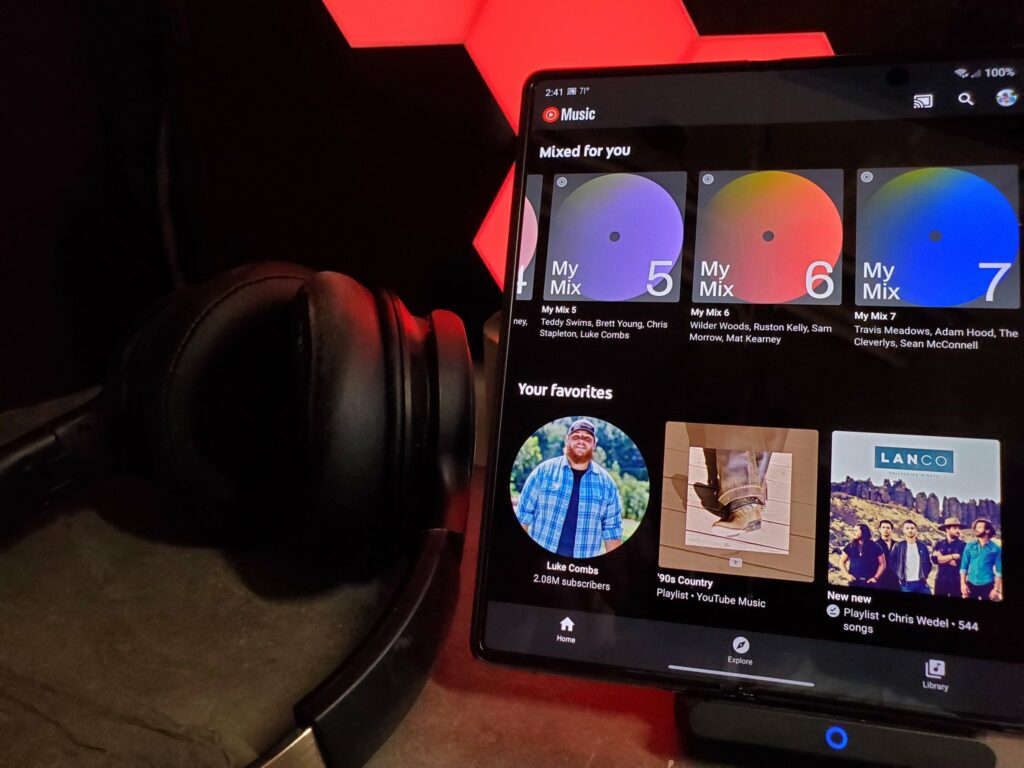

This endeavor has also placed a strong emphasis on improving the user experience. Along with Shorts, the platform’s vice president of product Adam Smith lists a number of subscription plans and features designed to pique fans’ interest, such as the extensive library of music content not found on competing services, which can include concerts, TV appearances, radio sessions, and premieres and exclusive content like “Afterparties” (where an artist holds an online event for a song or video). Additionally, there are features like “Meet” (where fans can watch videos together), “Foundry” and “Artists on the Rise” (programs for independent musicians to promote their artistic careers), curating of channel subscriptions, and a plethora of other services.

Smith claims that for the past seven years, “We’ve been building YouTube Music and Premium, anchored on this core set of features: being ad-free, having the ability to keep the videos or audio running when you’re in another app or on mobile, and being able to access it if, for example, you get on a plane and forgot to download the videos or audio you want. The objective is to enable users to take YouTube with them wherever they go, and we have a large team of professionals from the music industry working to provide what we think is the best music experience possible.

He and Cohen also mention events like the early-pandemic livestream of opera singer Andrea Bocelli’s concert at the Duomo in Milan, which Cohen calls “one of the greatest moments of my life” and YouTube’s yearly multi-channel livestream of the Coachella festival, which figuratively gives viewers the best seat in the house for free.

Another component of YouTube’s charm offensive targets fans and creators at roughly the same time because they are on opposite sides of the same issue: What do fans listen to when they have access to nearly anything on the planet? And how can musicians differentiate their music in the unfathomably large sea of choices?

Cohen provides an artist’s perspective to the discussion because he started working with artists like Run-DMC, the Beastie Boys, LL Cool J, and many more at Def Jam’s sister business Rush Management in the 1980s. Since social media has become so popular, artists are now practically forced to undertake another full-time job in addition to creating music in order to promote their professions and interact with listeners.

The “small print,” he claims, “for an artist nowadays is [producing] likes, clicks, subscriptions, all of these taxing things they need to do to find their audience, which they didn’t sign up for.” “I think a lot of them are really struggling, and the labels are struggling as well. Another issue that we hope to assist clarify and resolve is that. I want musicians to be free to concentrate more on composition and honing their craft rather than having to be always “on.”

For admirers The availability of options, he claims, is one of the main problems. This is the reason I’m so enthusiastic about Shorts. Shorts is so addicting that in many ways it makes me feel like I’m digging through a crate of records and pulling albums out, wondering what’s next. And my goal is to draw fans, or customers, to our YouTube main area so they can watch a premium music video, an interview, a live performance, or anything else that starts to forge a stronger bond with fans.

Increased competition in the digital market, especially in streaming, which has massively taken over as the primary global source for music consumption in barely a decade, is unquestionably in the best interests of the music industry. The rapid rise of YouTube and Amazon Music is quickly leveling the playing field after years of near-fealty to Apple’s iTunes and more recently to the troubled market leader Spotify. It also indicates an effort to counter what many in the music industry perceive as the next major threat, from TikTok, which is preparing to launch its own streaming service and is the most recent platform of many to tangle with the industry over royalties.

At the very least, Cohen is saying what the music business wants to hear, even though there will always be some skepticism when dealing with one of the richest and most powerful corporations in the world – in this case, YouTube and Google’s corporate parent, Alphabet. He ends by saying, “Our objective is to become the music industry’s primary source of revenue.”