Paul Johnson’s life was similar to that of every other struggling musician—he hustled, worked various jobs, and picked up gigs. Then one of Spotify’s Fresh Finds playlists, created to highlight up-and-coming musicians, included his cozy acoustic folk-pop song “Firework.”

Spotify and other streaming services make significant investments in playlists, from the journalistic RapCaviar to the algorithmically created Discover Weekly (which forecasts what new music members may enjoy) (the most desired real estate in hip-hop). Playlist placements are widely sought after because of how many streams they generate—in RapCaviar’s case, more than 7 billion in five years—and how they introduce music to new listeners. Johnson benefited from the latter.

His first playlisting increased his daily stream count from a few thousand to 20,000, and as his music appeared on more and more playlists, it eventually reached hundreds of thousands. He currently makes about $200,000 a year as a result of this exposure, primarily from streaming revenues. For Paul, that’s brilliant. But it’s a Horatio Alger tale, just like practically all musical accomplishments. Spotify wants you to think that the rise from poverty to wealth is the result of brilliance and hard effort, but it actually takes a lot of luck. Neglecting that luck component shows how challenging it is for musicians to support themselves with streaming revenues—and how many talented, hard-working people will never be able to do so.

One of the few times in the history of recorded music when power went in the direction of musicians occurred just before the streaming age started. Despite the fact that many of them experienced a severe economic downturn at the time, the democratization engendered by digital technology and the internet also made record companies feel under pressure to end abuses they had been doing for years.

Now, though, the recorded music industry is becoming an hourglass once more, with streaming services at the core. The streaming platforms are positioning themselves to do the same as the music industry is set up to allow labels and publishers to take home the majority of the value of music as they get more dominant.

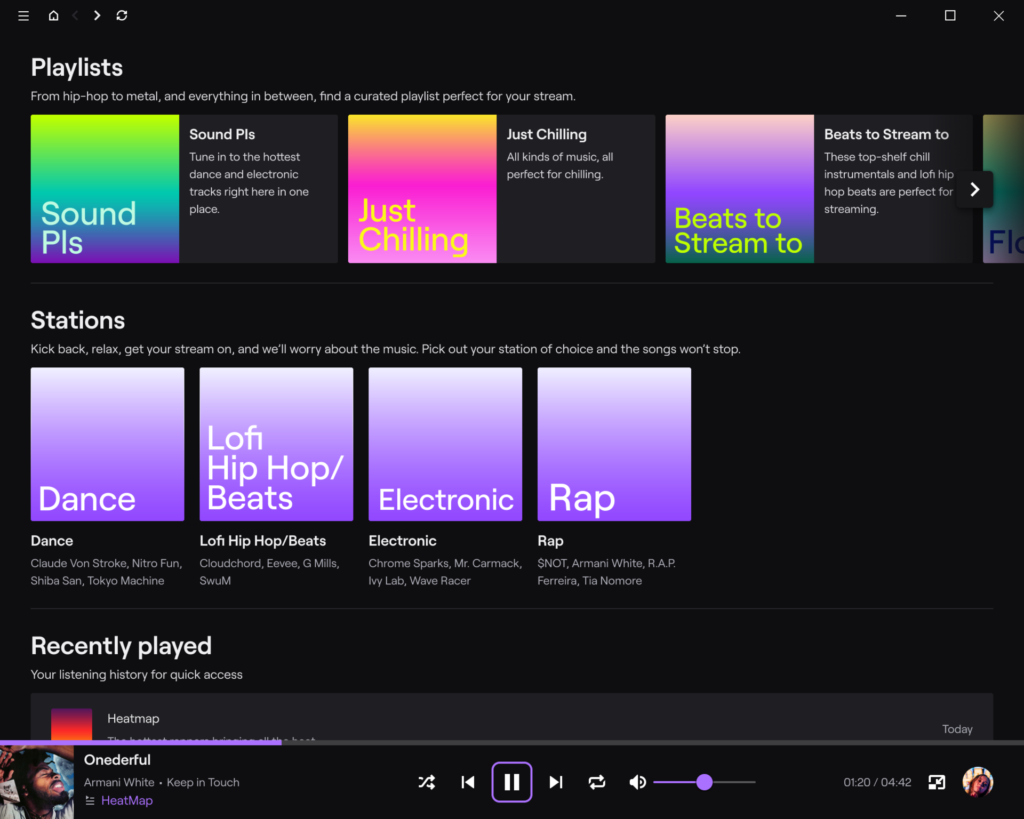

The most dominant, Spotify, informs investors that it intends to use its listeners to drive a significant digital ad play that would position it as the third-largest market leader, behind Google and Facebook. In order to gather what the company claims to be members’ real-time mood and activity data, it promotes playlists with names like Mood Booster, Happy Hits, Life Sucks, and Coping with Loss, then flogs it to sell ads.

This assertion, however, is very definitely false since, like the rest of Big Tech, Spotify is better at convincing advertisers that it has a mind-control ray that can force people to purchase goods than it is at actually convincing customers to do so. The real money will be made when Spotify acts as a middleman between listeners and performers. And a key component of its capacity to do so will be the very same playlists that earned Paul Johnson and other musicians their breakthrough success.

Listeners are promised the ability to access virtually any music via streaming. But instead of making their own choices, subscribers to streaming sites are increasingly listening to playlists created by algorithms or human curators. Playlists are becoming more and more common, as noted by the International Federation of Musicians: “There is one playlist for every minute of the day: wake-up, breakfast, work-out, relaxation, meditation, running, partying, etc. With only one button push, music can be played for the next 30 minutes, a whole evening, or the entire night.

In fact, playlists have grown to be so crucial that leaving one out can cause even megastar albums to fail (as Katy Perry discovered after Spotify blackballed her for giving rival Apple Music a brief exclusivity, evoking Amazon’s practice of cutting off publishers who wouldn’t give it sizable discounts). The same problems with gatekeeping that existed in media like radio are simply being duplicated, according to music journalist and pundit David Turner. “The tone of playlisting moved very swiftly in the last couple of years, from exhilaration to disillusionment,” he says.

Old power disparities are imported by playlist culture. Only one woman-led song was included on RapCaviar’s developing 50-track playlist over four weeks when journalist and music critic Liz Pelly investigated the gender of the artists featured on Spotify’s most popular playlists. Other top lists fared little better. American voices are also given priority in the largest editorial playlists across all platforms: According to a recent survey, roughly half of all bands that Spotify featured were from the US.

At 67 percent, it was even higher for Amazon Music. Additionally, the system frequently aids in ensuring that performers represented by the biggest labels receive the most publicity. Since platforms must remain on the good side of the majors to secure favorable terms the next time their license is up for negotiation, their personnel has direct access to editorial teams to market songs to them. Having saying that, the majors don’t necessarily get their way. The top 10 percent of streaming are now shared by more artists than ever before, which means that the top 40 pop singles are receiving fewer streams while everything else is receiving more.

The entire sound of music is changing as a result of streaming. Spotify wants its customers to listen as much as they can, and one method to do so is to provide them with “streambait,” or background music that may be played nonstop all day long. To that purpose, Spotify promotes undemanding selections such as Peaceful Piano, De-stress Chill, Chill Hits, Chill Vibes, and Chill Rap. Musicians are encouraged to write uninteresting, forgettable songs in order to achieve the massive volume necessary to support themselves through streaming. Even song length, which has decreased significantly during the streaming age, appears to be influenced by per-stream revenue. Twenty-five songs, averaging slightly over three minutes each, make up Drake’s 2018 album Scorpion.

Spotify is teaching us to delegate the choice of what to listen to by directing users toward playlists. The more streaming begins to resemble radio, the more users will immediately go to Spotify’s Viva Latino!, Baila Reggaeton, or Rock Classics. The difference is that there are many DJs that are passionate about discovering fresh local talent on radio, where there are thousands of them. With streaming, each channel is just programmed by a single anonymous global behemoth.

As Amazon attempted to disintermediate publishers by encouraging writers to publish directly, this development poses a similar threat to artists and record companies. A music culture relying on playlists is dependent on Spotify, whereas a music culture dependent on albums is dependent on record labels, according to Liz Pelly, who has been highlighting this risk for years. Passive listeners are less likely to develop relationships with successful performers or actively seek out their performances. Instead, consumers simply keep adding songs to playlists that promise more of the same and agree to play whatever replaceable artists are added after them.

As streaming platforms gain greater power over what is played, they are more able to take value away from artists, labels, songwriters, and publishers. That muscle is already being used by Spotify. Leading ambient acts like Brian Eno and Bibio have been sidelined in favor of pseudonymous songwriters and performers with no web presence but millions upon millions of song plays on its ambient playlists.

According to one research, these unidentified viral artists, who are all associated with the Swedish production company Epidemic Sound, are responsible for more than 90% of the tunes on Spotify’s ambient chill list. Nearly 3 billion streams have been accumulated by the top 50 artists. To put that figure into perspective, consider that RapCaviar, the most well-known playlist in streaming, only recently surpassed 7 billion listens on Spotify.

The rumor is that Spotify favored Epidemic Sound’s songs to increase margins after agreeing to lower than usual royalties with the label. According to a former insider at Spotify, the practice is “one of many internal initiatives to minimize the royalties they’re paying to the major labels,” according to Variety. This can save a lot of money: According to Rolling Stone, if Spotify had been paying industry-standard rates, it would have needed to pay out around $5 million in royalties only to the top 10 of these fabricated musicians.

As part of its “two-sided marketplace,” which enables it to sell both listeners and artists, Spotify has also started collecting co-op, a genteel term for payola, from creative producers. Similar to other internet companies, Amazon extorts publishers for their advertising expenses. Famously, Facebook first urged businesses to utilize it to interact with customers before abruptly requiring them to pay for access.

Investors are betting that Spotify can solidify its position in the recorded music sector with these kinds of tactics. Even though it has been losing money annually since its inception, its stock price nonetheless increased twofold after its initial public offering in 2018. Investors think it will acquire enough market dominance, like Amazon did, to be able to set rules and take more of streaming’s lucrative streams away from artists and labels. In addition, those rivers are just becoming wider: according to Goldman Sachs, the streaming market will reach $37 billion by 2030.

Spotify could succeed, according to venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz: “Music labels have traditionally demanded specific economics from streaming services, but if Spotify’s existing large user base continues to gain share, the negotiation could flip, allowing Spotify to achieve meaningfully differentiated economics relative to the competition.”

A little over a third of the market is controlled by Spotify. Big Tech dominates the remaining market, including Apple (19%), Amazon (15%), Tencent (in a joint venture with Spotify, 11%), and Google (6 percent). The same playlist culture is being promoted by these other players for the same reasons. Together, they are confident that they can make the music industry take on its familiar hourglass form, but this time with them at the heart.

If things continue the way they are, it will be difficult to stop them. Numerous motivated, artist-focused individuals are eager to create substitute platforms that are better for artists but are prevented from doing so by extremely high entrance hurdles. You should have sizable financial reserves if you intend to launch a streaming service. The licensing of music is absurdly complicated. The owners of sound recordings and the underlying compositions must be credited separately, according to separate rules.

You must personally negotiate sound recording licenses with all significant distributors and navigate all the red tape involved in obtaining the mechanical rights to the underlying songs in each nation where you intend to do business. Leading music industry attorney Amanda Harcourt reveals how difficult it is for small and medium-sized businesses to obtain just the composition rights necessary to launch a streaming service in Europe. She calls the process “dreary” and “unduly complex.”

Peer-to-peer software providers and streaming platforms without a license were widely available in the early 2000s. Record sales fell off a cliff, the recording industry panicked, and decided to pursue them in court to the death, pushing them out of business. They characterized music lovers as unethical criminals concerned with getting everything for free as a result of the correlation between these technologies and the decline in earnings.

But once licensed streaming became an option, as evidenced by its explosive growth, it was the promise of quick access to all of the world’s popular music that was really luring people. The transition could have been much less painful if the recording industry had seized the chance to collaborate with lawmakers to simplify licensing for these new distribution channels at the time, and we would now have licensing rules that were more suited for purpose than the convoluted mazes we currently have.

These licensing challenges, according to Spotify CEO Daniel Ek, are one of the main growth constraints for the service. Undoubtedly, but these mazes continue to be advantageous to it. Yes, they constrain Spotify’s growth, but they also prevent competitors from ever establishing themselves. Due to the fact that paying these high transaction fees prevents Spotify from having to engage in true competition, they are essential to its own anticompetitive flywheel.

Additionally, as we previously observed in the chapter, the major record companies regularly blackmail prospective competitors in order to provide them the licenses they require to launch, further raising the barrier to entry. That explains why the only significant competitors for Spotify are wealthy tech behemoths—they’re the only ones with the means to do so.