The unsettling paintings of the Swedish artist Simon Stalenhag combine natural landscapes with the strange futuristic imagery of enormous robots, enigmatic industrial equipment, and extraterrestrial animals. This week, when Stlenhag discovered that artificial intelligence had been employed to copy his style, he seemed to suffer some of his own dystopian fear.

Andres Guadamuz, a reader in intellectual property law at the University of Sussex in the UK who has been researching the legal ramifications of AI-generated art, committed the act of AI mimicry. He created photographs that resembled Stlenhag’s eerie aesthetic using a website called Midjourney and shared them on Twitter.

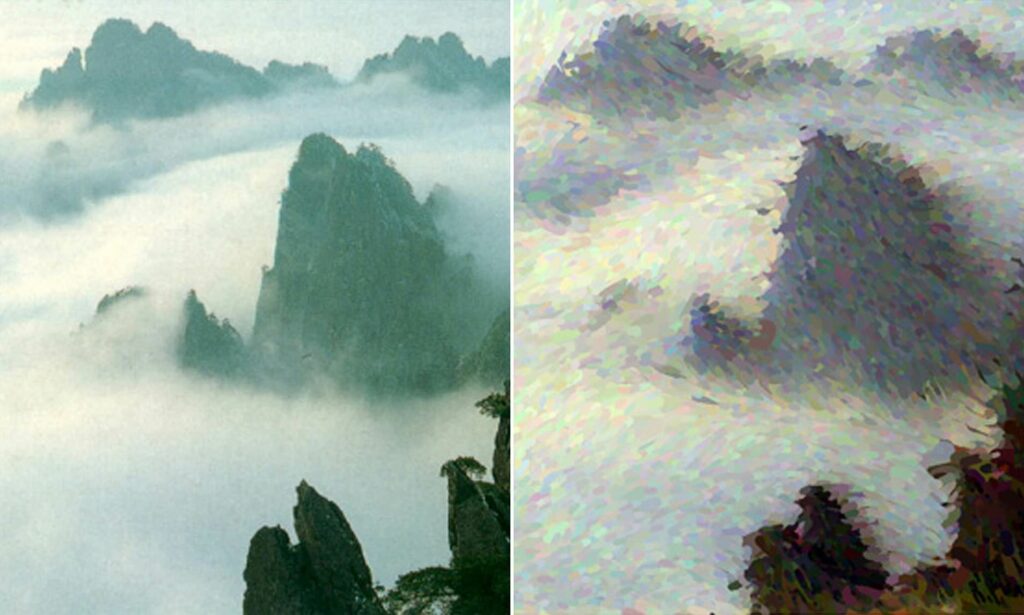

Guadamuz claims he made the photos to draw attention to the moral and legal concerns that algorithms that produce art can bring up. Using machine learning algorithms that have ingested millions of annotated photos from the web or open data sets, Midjourney is just one of many AI programs that can produce art on demand in response to a text input. After receiving that training, they are able to create practically any arrangement of items and settings in addition to accurately mimicking the individual artistic styles of many artists.

Stalenhag was the artist Guadamuz says he chose for his experiment since he had previously criticized AI-generated art and could be anticipated to react. However, he claims that his intention was not to enrage the artist or elicit a reaction. After the occurrence, Guadamuz argues in a blog post that lawsuits alleging infringement are unlikely to be successful since, unlike an artistic style, a work of art cannot be protected by copyright.

Stalenhag did not find it funny. This week, he expressed his distaste for artificial intelligence (AI) art in a series of tweets, saying that while it is a “cornerstone of a living, artistic culture,” it “reveals that that kind of derivative, generated goo is what our new tech lords are hoping to feed us in their vision of the future.”

Stalenhag received a public apology from Guadamuz, who also claims to have removed the offending tweets. Guadamuz claims that some Twitter users who disapproved of his action sent him nasty messages, including a death threat. He claims that what was first intended to be a thought-provoking experiment turned out to be an assault. Guadamuz quips, “By day I’m a bored mild-mannered academic, but by night I become a supervillain wrecking artists’ livelihoods… or something.”

Stalenhag claims in an email that he disagrees with the way Guadamuz presented his act but accepts the latter’s apologies. The artist believes that while the AI images resemble his creations in a novel way, it is not plagiarism and that technologies like the one utilized may be beneficial for developing fresh artistic concepts.

However, Stålenhag disapproves of the way new technology might be used to enrich CEOs and already-powerful IT businesses. The newest and most dangerous of these technologies, he claims, is AI. “It literally steals lifetimes of labor by artists without their permission and utilizes that data as the fundamental component in a new form of pastry that it can sell profitably with the only goal of lining the pockets of a group of boat owners.”

Decades of algorithms have been employed to create art, but a new era of AI art started in January 2021 with the release of DALL-E, a program that exploited recent advances in machine learning to create straightforward visuals from a string of text.

The business unveiled DALL-E 2, which can create images that appear to have been created by human artists, in April of this year. In July, OpenAI declared that DALL-E would be made available to everyone and allowed for commercial usage of the photos.

Using keyword filters and algorithms that may identify specific types of photographs that might be deemed objectionable, OpenAI limits what users can do with the service. Similar programs have been created by others, such as Midjourney, which Guadamuz uses to imitate Stlenhag, but which may have different usage guidelines.

More artists are raising concerns about the propensity of AI art generators to copy the work of human creators as access to them widens.

RJ Palmer, a concept artist for the film Detective Pikachu and a specialist in creating fanciful animals, says he was curious enough to check out DALL-E 2 but also grew concerned about what such AI tools would mean for his line of work. Later, he was surprised to observe Stable Diffusion users exchanging advice on how to create art in various styles by adding artists’ names to a text prompt. Palmer calls it “simply mean-spirited” when people “feed work from living, working artists who are, you know, struggling as it is.”

Digital artist David Oreilly, who has criticized DALL-E, claims it feels unethical to use these technologies that draw on previous work to produce new pieces that are profitable. He claims that “they don’t own any of the content they recreate.” “It would be like charging for Google Images.”

CEO of the Danish stock photo company Jumpstory, Jonathan Lw, said he doesn’t get how AI-generated photographs may be utilized for profit. In addition to being genuinely frightened and apprehensive, he admits that he is attracted by the technology.

According to Hannah Wong, a representative for OpenAI, the business’s image-creation service is utilized by numerous artists, and the company solicited their input when developing the tool. The statement read, “Copyright law will need to adapt to AI-generated works in the same way it has in the past to new technology.” “We look forward to engaging with artists and lawmakers to help defend the rights of creators,” the statement reads. “We continue to seek their viewpoints.”

Guadamuz anticipates lawsuits, despite his belief that it will be challenging to bring a claim against someone who uses AI to imitate their work. I’m confident that there will eventually be all manner of litigation, he asserts. He claims that using a character’s likeness, such as Mickey Mouse, as a trademark infringer could prove to be more problematic legally.

Other legal professionals are less confident in the legality of imitations produced by AI. According to Bradford Newman, a partner at the law firm Baker Mckenzie who specializes in AI, “I might see litigation developing from the artist who claims ‘I didn’t grant you permission to train your algorithm on my painting’.” “Who would win such a case is entirely up for debate.”