Leonidas Nzigiyimpa, a conservationist, believes “you can’t control what you don’t know.”

He continues, “We need to apply new technology to improve the condition of forests.”

The small central African nation of Burundi’s main warden of five protected forestry zones is Mr. Nzigiyimpa.

He has been collaborating with regional communities to maintain and conserve the forest for the past 20 years. When he talks about the fresh scent and natural beauty of the places, his countenance beams. He describes it as being pure nature.

Mr. Nzigiyimpa must take into account a variety of elements when performing his duties, including staffing levels and finances, as well as monitoring the effects of economic and societal factors on the environment, biodiversity, and climate change.

He currently employs the most recent version of the Integrated Management Effectiveness Tool, a free piece of software, to assist him in tracking and recording all of this.

A team called Biopama created the instrument expressly for such environmental activity (Biodiversity and Protected Areas Management Programme). Both the European Union and the Organization of African, Caribbean, and Pacific States, which has 79 members, support this.

So, according to Mr. Nzigiyimpa, “we use this kind of tool to train the site managers to use it to collect excellent data, to analyze this data, and to take good judgments.”

It’s critical to monitor and safeguard the world’s forests for all local populations and economies, not just those that are negatively impacted. Restoring forests could aid in the fight against climate change as deforestation contributes to it.

According to the United Nations, the world’s forests are losing about 10 million hectares (25 million acres) each year.

According to the World Wildlife Fund, this deforestation is responsible for 20% of all global carbon dioxide emissions, and it adds that “by limiting forest loss, we can reduce carbon emissions and fight climate change.”

The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration was launched last year by the UN in an effort to try and restore forests and other natural habitats throughout the world. As a result, various nations, businesses, and organizations have pledged to take steps to stop, slow down, and reverse the global ecological degradation.

Yelena Finegold, a forestry officer for the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), asserts that simply promising to rehabilitate the environment is insufficient. “Responsible planning of how that ecosystem restoration will take place is required, as are investments in restoration, actions on the ground made possible by those investments, and monitoring systems in place to track that ecosystem restoration.”

New digital tools to better collect, sort, and utilise data have emerged in response to the increased attention on maintaining forests.

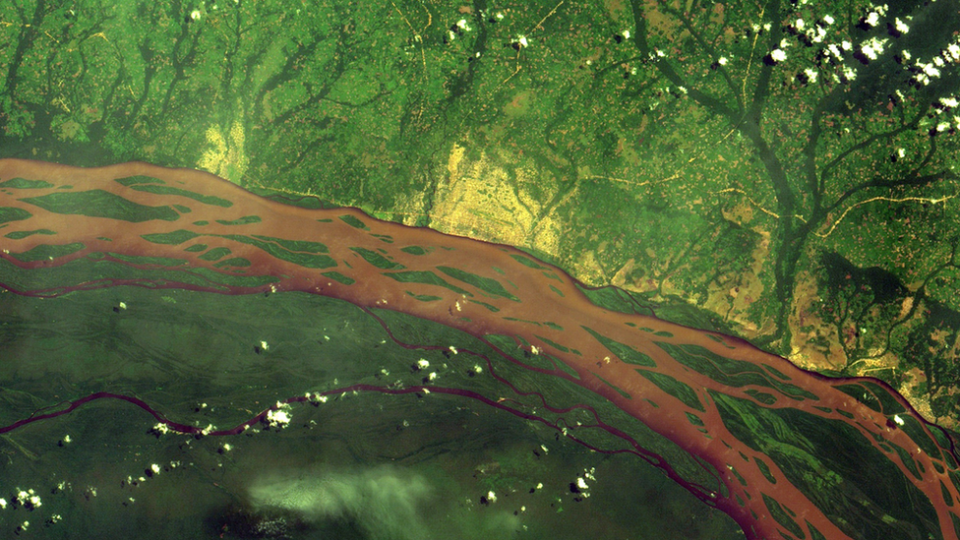

One of these is the Framework for Ecosystem Monitoring (Ferm) website, which belongs to the FAO. The website, which was introduced last year, highlights changes to forests all across the world using satellite photography. Any internet user, whether a scientist, government employee, business owner, or member of the public, has access to the maps and data.

NASA, the US space agency, and its Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation system are important data sources for Ferm. This abbreviation, often known as Gedi for short, is pronounced like the term Jedi from the Star Wars movies. Its tagline, “may the forest be with you,” carries on the theme of that film series.

The technology itself is undoubtedly very science fiction in real life. The Gedi project’s co-leader and assistant professor of geographic sciences at the University of Maryland, Laura Duncanson, explains that they “fire laser beams at trees from the International Space Station.”

Dr. Duncanson, a well-known authority in remote sensing, continues, “We use the reflected radiation to map forests in 3D, including their height, canopy density, and carbon content. “This is an interesting new technology because, while we have been able to witness deforestation from space for decades, Gedi allows us to more precisely allocate the carbon emissions linked to forest loss.”

The US company Planet, which manages more than 200 camera-equipped satellites, also provides maps and data to Ferm. Every day, these snap about 350 million pictures of the Earth’s surface, each one spanning a square kilometer.

Planet is also directly employable by organizations and governments all over the world. Its cameras may be used to examine everything from droughts to agricultural, energy and infrastructure projects, and monitoring crucial infrastructure, such as ports, in addition to keeping an eye on forests.

A colleague forestry officer with the FAO, Remi D’Annunzio, claims that the abundance of space imagery “has significantly impacted the way we monitor forests, because it has led to incredibly reproducible observations and extraordinarily frequent revisits of areas.”

Basically, we can now obtain a complete image of the Earth every four to five days because to the combination of all these publicly accessible satellites, he continues.

Pilot programs in Vietnam and Laos that aim to combat illegal logging are examples of how all this current near real-time monitoring via Ferm is being used. When new deforestation is discovered, alarms are transmitted to the mobile phones of rangers and community workers who are on the ground.

“Now, what we’re really trying to do is not just understand the volume of forests being lost, but where is it exactly being lost in this district or that,” explains FAO forestry officer Akiko Inoguchi. “So that we can monitor loss, and even prevent it in near real-time, from getting worse.”