Many people who have already listened to the MBW’s most recent Talking Trends podcast may have noticed a particularly important statistic for the contemporary music industry.

According to MBW’s interpretation of Goldman Sachs’ most recent Music In The Air study, TikTok would pay labels and artists that have recorded music rights a total of about $179 million in 2021.

Here’s how MBW calculated that:

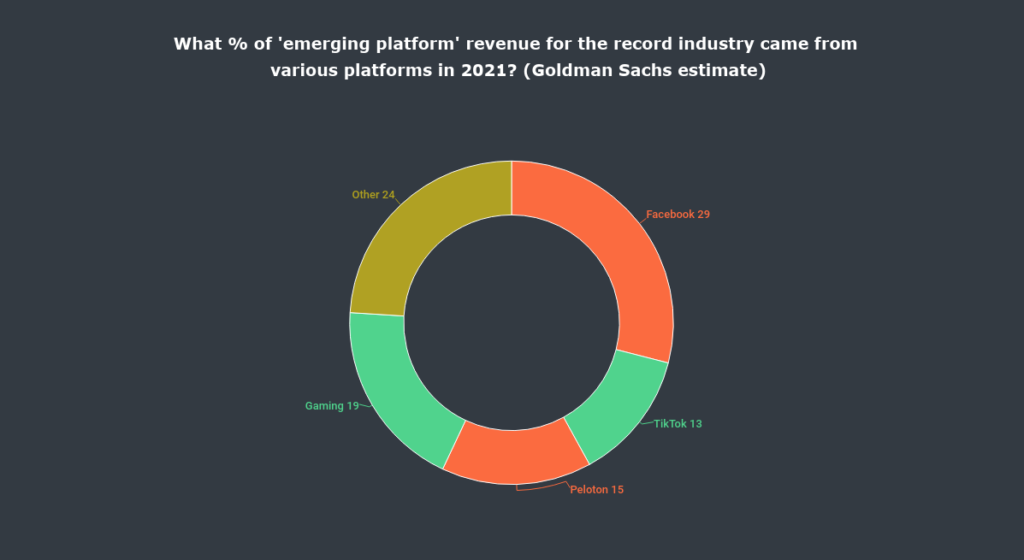

- According to Goldman Sachs, TikTok contributed an estimated 13% of record labels’ “emerging platform” revenues in 2021 (see below; Facebook/Meta contributed 29%);

- In turn, Goldman estimates these “emerging platform” revenues made up 30% of all ad-supported streaming revenues paid to the recorded music business in 2021;

- According to IFPI numbers, ad-supported revenues paid to the record business in 2021 amounted to approximately $4.6 billion;

- 30% of $4.6 billion is $1.38 billion

- 13% of $1.38 billion is… $179 million.

Now. In 2021, TikTok produced close to $4 billion in global revenue, according to Bloomberg. In 2022, TikTok is predicted to treble this amount to $12 billion.

The amount TikTok is anticipated to have paid recorded music rights holders ($179m) works out to 4.5 percent of the entire 2021 turnover.

Now would be a good time to compare TikTok to one of its main competitors, a platform that the modern music industry likewise largely relies on.

that is, YouTube.

YOUTUBE VS. TIKTOK: MUSIC INDUSTRY PAYOUTS

In the first 12 months of 2021, YouTube made $28.84 billion in advertising revenue, according to financial documents filed by parent company Alphabet.

And in June of last year, YouTube asserted that in the previous 12 months, it had paid out over $4 billion to owners of music rights.

In 2021, that $4 billion will account for 13.9% of YouTube’s ad income.

There are a few restrictions on using the calculation, though.

- Firstly, the $28.84 billion figure is only YouTube’s advertising haul; it doesn’t include the additional billions the company pulled in during 2021 via subscriptions to services such as YouTube Music.

- In addition, Goldman Sachs’ TikTok estimate, crucially, was just for the money it paid recorded music rightsholders. YouTube’s $4 billion figure, by contrast, covered money paid to both publishing/song rightsholders, and recorded music rightsholders.

So let’s assume for the purposes of argument that a third of this sum went to publishers and songwriters. (By all accounts, that’s an OTT suggestion; according to the majority of industry estimates, publishers/songwriters receive anywhere between a fifth and a quarter of all royalty payments when it comes to on-demand streaming.)

In the 12 months leading up to the end of June 2021, this would mean that YouTube paid recorded music rights holders $2.64 billion.

That $2.64 billion sum would represent around 9.1 percent of YouTube’s total advertising revenue for the calendar year 2021.

Underpinning any comparison between how much TikTok pays the music industry vs. how much YouTube pays the music industry lies a crucial difference: The two contrasting models via which both companies distribute money to record labels and music publishers.

- YouTube’s ads business pays the music industry a revenue share of any ad-triggering (monetized) play of a video that uses music on its platform;

- TikTok, by contrast, does not pay out a share of advertising based on plays. Instead, it licenses music from major record companies via individual “blind check” payments, each of which covers a certain period of grace. In these grace periods, TikTok (and its users) can incorporate copyrighted music as much as they please.

Those “blind checks” from TikTok, according to Goldman Sachs, appeared to total about $179 million for the record industry in 2021 on an annualized basis.

Ole Obermann, the head of music for TikTok globally (seen inset), has defended the company’s decision to forgo using a revenue-share approach to compensate music rights holders.

While claiming that TikTok is a “strong marketing and promotional tool for musicians of all genres,” Obermann said in a statement: “We’re not a streaming platform, and we do not provide a subscription model.”

The contention that TikTok is just a “promotional platform” that “starts the fire” of popular songs on other streaming services rather than a site where people actively play or consume music will be an important topic of discussion for the music business in the months and years to come.

So let’s move this discussion along by focusing on the top song of the summer of 2022.

Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God) by Kate Bush is currently extremely popular throughout the world, almost completely because of a sync on a Netflix series (Stranger Things).

Running Up That Hill continues to be the most-streamed music on Spotify worldwide over two months after that killer sync made its premiere on May 27.

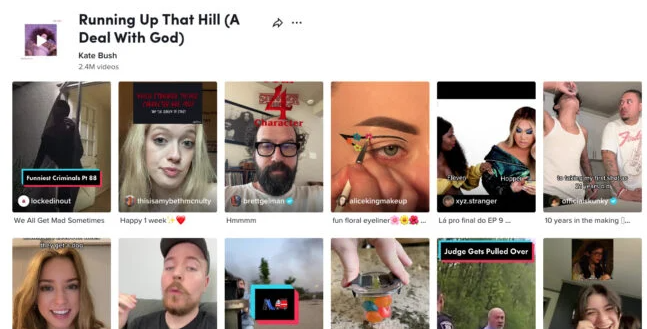

The track has now been featured in at least 2.4 million different videos on TikTok, mostly as a result of that sync exploding (see below).

The large sums are about to appear.

Just the Top 1,000 most popular of these 2 million+ films have received a total of 4.93 billion plays to date, according to ChartMetric statistics examined by MBW.

(It is therefore safe to conclude that Kate Bush’s song has been played on TikTok more than 5 billion times to date, taking into account the whole 2.4 million+ videos, in addition to the Top 1,000 TikTok videos using Running Up That Hill.)

- Key point 1: Due to there being no revenue share / royalty-based agreement between her distributor (Warner Music Group) and TikTok, Kate Bush is not getting paid for any of those plays. (Outside, that is, of the aforementioned ‘blind check’ sent to Warner by TikTok at a certain point in the past. And only if Warner has paid any of it through to the artist.)

- Key Point 2: Kate Bush’s track has over 5 billion (unpaid) views on TikTok. 5 billion! The song has just over 400 million plays on Spotify, despite being that platform’s global No.1 for weeks. So is TikTok really ‘promoting’ Running Up That Hill? Or is it in fact cannibalizing plays of the song that could otherwise have happened on ‘revenue share’ streaming platforms like Spotify?

Concerns from the music industry over the second important factor above are increased by the fact that TikTok videos are no longer just “30/60 second teasers” for music recordings.

TikTok stated in February of this year that its videos may now be up to 10 minutes long.

Less than a year had passed since July 2021, when TikTok increased the maximum duration of videos to three minutes. (Sixty seconds was the predetermined maximum.)

How crucial is this tactic for TikTok/Bytedance, allowing users to post videos long enough to include two or even three complete songs?

You merely need to create a TikTok account to find out.

When you do this, one of the first things you’ll notice is a cheery instruction message hovering next to your “Upload” button, reminding you that videos can now be 10 minutes long on TikTok and enticing you to take advantage.

Additionally, statistics suggest that TikTok is increasingly overpowering Spotify playlists as the main influencer of Gen Z’s music preferences. This presents another bogeyman for the music industry to contend with.

Take a look at these alarming numbers from a Media Research study conducted in Q3 2021:

- Just 10% of 16-19-year-olds globally listen to curated playlists on streaming services (like Spotify);

- In contrast, 24% make their own playlists, and one-third use TikTok each DAY

TikTok may not only be stealing Spotify plays; it may also be stealing influence among the potential Spotify subscriber base of the future.

At the risk of repeating myself, Spotify equals income sharing with labels and artists while TikTok does not.

Let’s make sure we’re clear on all of that:

- The world’s most popular song of the moment – Running Up That Hill – has been played over ten times more on TikTok (5bn+) than it has on Spotify (≈400m);

- TikTok videos are now permitted – and indeed, encouraged – to be long enough that the whole song could be included twice over;

- There is no royalty (revenue share) being paid for plays of Running Up That Hill, because TikTok argues it’s a “promotional” platform and “not a streaming service”;

- Yet TikTok itself (via TikTok For Business) proudly admits that “88% of TikTok users said that sound is essential to the TikTok experience”, and that it’s “nearly impossible to separation [sic] a TikTok from its sound, or else the video no longer makes sense”.

All of that sounds like it might be worth a little bit more to the music industry than $179 million annually, don’t you think?

especially given that TikTok is predicted to generate $12 billion in sales in 2022, approaching the size of the whole US record industry ($15 billion in revenue in 2021)?

You might be able to understand why prominent figures in the music industry are beginning to voice their concerns about the power dynamics with TikTok.

Even without a revenue-share agreement, TikTok’s “blind check” payments may have seemed like “easy money” for record labels during the last few years.

But to some, that picture is already beginning to resemble an industry that is sleepwalking towards a generational error and failing to see the signs.

“THE LAST TIME WE LET A COMPANY OF THIS SIZE AND POWER RUN AWAY WITH THINGS WITHOUT PAYING US PROPERLY WAS MTV.”

One significant record label source just gave me a concise summary of the situation, as I noted on the Talking Trends podcast.

Soon, TikTok will be too big and strong for us to compel it into a revenue-share agreement, he predicted.

“MTV was the last firm of this size and strength that we let to get away with not paying us correctly,” the company said.