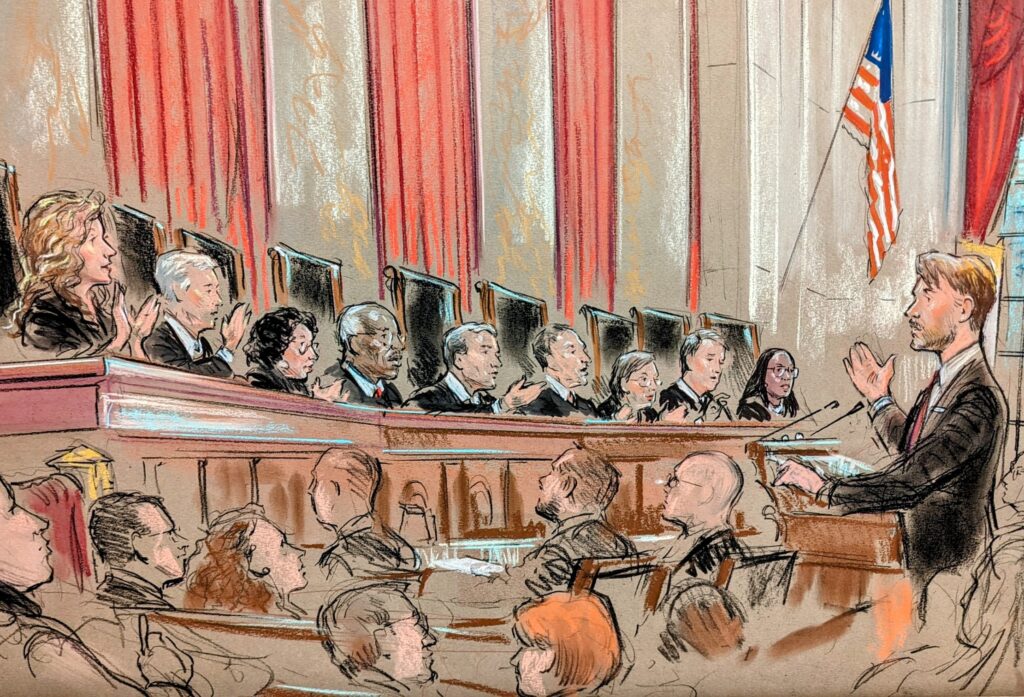

The Supreme Court battled Monday morning with new legislation in Florida and Texas that impose broad new restrictions on digital companies’ power to remove user posts.

During nearly four hours of debate, some justices raised concerns about aspects of both legislation, but it was unclear if at least five of the court’s nine judges would block the statutes.

Both states’ laws make extensive attempts to bar digital corporations from limiting expression in certain instances. In both cases, Republican lawmakers championed the restrictions, claiming that digital giants were disproportionately suppressing conservative viewpoints.

READ MORE: Wendy Williams’ Documentary Sends Social Media Into Chaos

Florida Attorney General Henry Whitaker defended the state’s law, claiming that it upheld the First Amendment by “promoting and ensuring the free dissemination of ideas.”

Former US Solicitor General Paul Clement, who represented the internet industry, argued that the First Amendment protects platforms’ capacity to exercise editorial control over the content available on their platforms.

READ MORE: Fans Of Paramore Are In A Severe Panic When The Band Removes All Of Its Social Media And Website

“When editors or speakers engage in viewpoint discrimination, that is their First Amendment right,” Clement went on to say.

“It is also extremely critical to the operation of these websites because, in order to be viewpoint-neutral, you must have materials that promote suicide as well as information that prevent suicide. Or, if you have pro-Semitic stuff on your site, you must also allow anti-Semitic materials on your site,” he continued.

Among other things, the Florida law imposes fines on social media corporations of $250,000 per day for “deplatforming” candidates for statewide office and $25,000 per day for other seats. (The measure defines deplatforming as a suspension lasting more than 14 days or a ban.) It also prohibits huge social media platforms from censoring posts by journalistic organizations based on content.

The Texas bill includes measures that prevent social media platforms with at least 50 million users from removing or suppressing lawful posts based on their viewpoint.

NetChoice and the Computer and Communications Industry Association challenged both laws on First Amendment grounds, arguing that private companies have the right to choose what speech to carry, including the right to suppress objectionable content, such as anti-vaxxer or racist posts. The Interactive Advertising Bureau supported the challenge, stating that businesses do not want to advertise next to objectionable posts.

A trial judge and three-judge panel of the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals issued a preliminary injunction declaring the majority of the Act unconstitutional. In Texas, a trial court overturned the statute, but the Fifth Circuit ruled that it should be reinstated. (The decision to reinstate the statute was stayed awaiting Supreme Court review.)

On Monday, the case reached the Supreme Court, where many judges appeared worried by regulations governing how social platforms — such as Meta, YouTube, TikTok, and X (previously Twitter) — handled information.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, for example, repeatedly challenged Florida Solicitor General Andrew Whitaker’s claim that the statute enhanced the First Amendment by prohibiting social media companies from “censoring” expression.

“In your opening remarks, you said the design of the First Amendment is to prevent ‘suppression of speech,'” the Supreme Court nominee said Whitaker.

“And you left out what I understand to be three key words in the First Amendment … ‘by the government,'” he said.

“When a private individual or private entity makes decisions about what to include and what to exclude, that’s protected generally editorial discretion, even though you could view the private entity’s decision to exclude something as ‘private censorship,'” Kavanaugh remarked at the time.

Other justices questioned the appeal’s procedural stance, claiming that the challenge to the legislation reached the Supreme Court prematurely because lower court judges barred the statutes before determining their full scope.

Some judges appeared to be concerned about whether the regulations could apply to services other than social media. For example, some justices questioned whether the Florida rule would extend to non-social networking sites such as Gmail or Uber.

U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, who urged for the measures to be blocked, conceded that Florida’s legislative sweep was imprecise.

“We think there’s a lot of ambiguity about what the state law requires,” Prelogar said in an interview.

According to Santa Clara University law professor Eric Goldman, co-director of the school’s High Tech Law Institute, the fact that judges have questioned the regulations’ relevance to services such as email indicates that they are struggling with them.

“The laws mostly baffled the justices due to the indeterminacy of who the law reaches and which functions are regulated (justices called the laws ‘sprawling,’ ‘broad,’ and ‘unspecific’),” he writes in a statement he sent by e-mail. “Because the statutes are so intricate and baroque, the justices are unsure whether they can now conclude that every component of the laws is unconstitutionally invalid. The judges’ inquiries made it plain that at least some portions are, but they also struggled with peripheral activities (such as ridesharing or email) that may or may not be covered by the legislation.

The court is scheduled to make its decision by June.

Radiant TV, offering to elevate your entertainment game! Movies, TV series, exclusive interviews, music, and more—download now on various devices, including iPhones, Androids, smart TVs, Apple TV, Fire Stick, and more.