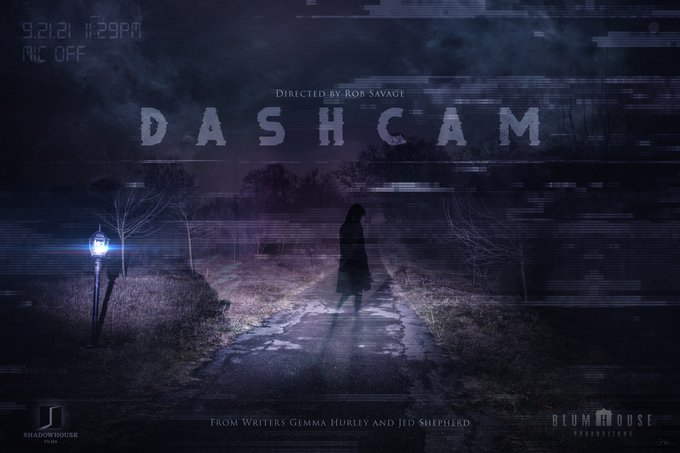

Rob Savage’s Dashcam is going to be the most polarizing horror picture of the year.

If the zeitgeist-grabbing Host, which was shot entirely on Zoom during the first COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, was best watched alone in the dark at home, Dashcam begs to be seen with a full and ready-to-be-scared audience on a Friday or Saturday night.

Annie, a foul-mouthed, MAGA hat-wearing anti-conformist and wind-up merchant, is the atypical protagonist of Dashcam, a deliciously crazy adrenaline adventure. She arrives in the UK to allegedly visit her friend Stretch (Amar Chadha-Patel), but finds herself unwittingly smack-bang in the heart of a strange tale involving an elderly woman named Angela (Angela Enahoro).

Annie Hardy, a podcaster, freestyle rapper, and Giant Drag frontwoman, plays the lead. “I’m portraying myself as an alt-right figure.” During a Zoom meeting with her director to discuss their grisly frolic, she reassures, “I’m not as much of a dickhead myself.” What she is, though, is a cyclone of energy who puts on a masterful display of bad taste parody. Imagine a bizarre misfit from a Harmony Korine or John Waters film being dropped into a found-footage horror film. There is no such thing as crossing the line with Dashcam, as viewers will find. There’s no such thing as a line.

Dashcam’s bizarre allure can be traced back to blockbuster horror sequels from the 1980s, such as Evil Dead 2 (1987) and Hellbound: Hellraiser II (1988). These films subverted their terrifying and dramatic predecessors by turning them aggressively comical and surprising the spectator. “I wanted this film to be in the tradition of those ’80s sequels that took a sophisticated original film and turned it into a very un-classy, large, noisy, kind-of-comedic sequel,” Savage adds. “This is the sequel to my Texas Chainsaw Massacre.”

Savage eloquently highlights the rich history and culture of horror filmmaking, provoking spectators. The director is unconcerned about Dashcam’s critical reaction or the possibility that it could be misinterpreted: a film does not have to condone what it depicts.

“I think if any genre should skirt the boundaries of being offensive, it’s horror,” he offers. “[By] pushing people to uncomfortable places, horror reflects the world as it is. What I want to say when people get offended, it’s like the poster quote from The Last House on the Left: ‘Keep repeating to yourself: it’s only a movie, it’s only a movie. It’s really meant to be a fun beer-and-pizza movie, where you laugh and gasp, and maybe if it offends you, that’s a good thing.”

For many of us, the epidemic has been a sad and painful experience, but it has also provided Savage with the opportunity to establish himself as a master of chills and thrills. Host, a computer screen horror film (an aesthetic offshoot of the found-footage subgenre) released in 2020, hit the spot with its traditional approach to conveying a ghost story. The film was a critical and commercial success, propelling Savage to Hollywood and landing him a deal with Blumhouse Productions (best known for the Paranormal Activity and Purge franchises).

The filmmaker is still astounded by the positive response to Host: “Host felt incredibly low-pressure.” Even if the movie wasn’t amazing, I thought we’d get credit for trying. I expected it to be a nice distraction during the lockdown, but I also expected it to be a little snooty, that it would be opportunistic and gimmicky – which it was – but the response… people coming together and applauding this movie was really surprising.”

Savage didn’t set out to make horror movies in the first place. Growing up in rural Shropshire, he aspired to be the next Andrea Arnold or Lynne Ramsay and worked a variety of jobs to save money for his first feature. “Growing up in the country, the film industry seemed a million miles away,” he says. “I was so naive about the process of making a film. You make a short [film] and maybe the BFI will fund you, then you make a feature and, if it’s excellent, you get to make another five or six years later. I had no idea about any of that.

“My first movie was Strings, this lo-fi, rigidly-made relationship drama I made when I was 17 or 18 [2012]. I learned to make movies on the fly: I was my own editor, my own cinematographer, doing all these different roles. The film is fine – it’s very much a film made by a 17-year-old.”

Strings earned Savage a BIFA (British Independent Film Awards) award, allowing him to sign with an agency and begin his ascent up the ladder. After five years, he realized he should be pitching pictures that people wanted to watch rather than trying to make “jerk-off arthouse flicks,” as he put it. The switch to horror proved to be a wise one, as Savage has established himself as a fascinating new voice in the genre in just two films. He acknowledges, “I’ve always loved horror.” “I admire Lucio Fulci just as much as Michelangelo Antonioni.”

Dashcam is a Livestream feed that is captured on iPhones (the accompanying text seen on the left side of the frame throughout the film was achieved ingeniously using a computer program). Hardy, who broadcasts Band Car on Periscope, is the brains behind the endeavor and the motivation for all of its subsequent bloodshed and lunacy. Her internet show mainly consists of her driving about Los Angeles and freestyling while behind the wheel, as her fans engage with her. Jed Shepherd, who also produces Hardy’s podcast Empath of Least Resistance, had a simple idea for Band Car as a horror movie.

“Jed showed me Band Car and said, ‘This would make a wonderful horror movie set-up,'” Savage recalled. “After some brainstorming, we came up with Annie picking up an elderly lady that she must transport from one location to another. The old woman’s role as both victim and aggressor struck a chord. ‘Don’t go outdoors or you’ll murder grandma,’ Boris Johnson was saying at the end of 2020. It felt like a very lighthearted thing to do.”

Dashcam was shot in Margate, Norfolk, and London towards the end of 2020, and most of it, notably the language, was improvised. Savage and Hardy both spoke about how much fun it was to make the picture (Savage recalls how some of the finest shooting days had him, Hardy, and their producer racing around the woods “just making stuff up”). The improv-heavy style of the production allowed them to alter and redo as needed with only a rough outline to guide them each day. Hardy was game to embrace this happy, guerrilla method of filmmaking, even though she was forced to do multiple takes, which she jokes was a little too much for her.

“We did a lot of takes because Rob makes you do it again and over.” Me? “Usually, my first take is the best,” Hardy proclaims. “The issue is,” the director responds, “the first take and the second take bear no similarity to each other since you never truly did the same thing again.” “I did so many takes because you did something completely different every time, and it inspired me to do a third and fourth take.” With each take, you became better and better.”

Hardy had a great time filming in Europe and also found time to work on her own creative projects. She declares, “British folks are my people.” “I often say I’m Budweiser in America, but I’m an imported beer to you guys.” Budweiser is a great beer in my opinion! I thought [shooting in England] was fantastic, except for the fact that it was quite chilly. I got to see Margate for the first time and slept at The Albion Rooms, a hotel with a recording studio owned by The Libertines. I didn’t have to go or do anything, and I was recording an album.”

Hardy had a great time filming in Europe and also found time to work on her own creative projects. She declares, “British folks are my people.” “I often say I’m Budweiser in America, but I’m an imported beer to you guys.” Budweiser is a great beer in my opinion! I thought [shooting in England] was fantastic, except for the fact that it was quite chilly. I got to see Margate for the first time and slept at The Albion Rooms, a hotel with a recording studio owned by The Libertines. I didn’t have to go or do anything, and I was recording an album.”

Was she frightened that people would confuse the fictional Annie with the real-life Annie? “They’ve already done so. Everyone these days thinks in black-and-white terms, and [Dashcam and her character] fall into that category. Although the character’s name is my own, there are some elements and things [in the film] that I would never say [in real life]. It’s a film, after all. People, on the other hand, no longer understand the concept of movies and believe that this is real life. So it’s possible they don’t realize it’s a hoax.”

Hardy goes on to say that she’s the ideal star for a horror film since “my life has seemed like a true-life horror film at times,” in her opinion. What do you mean by that? “I’ve had stalkers threaten to come to my house and commit murder-suicide,” she says. “I’m sure there’ll be an uptick after the movie comes out,” she observes, between cynicism and joking.

So many of today’s horror directors have either forgotten or dismissed the art of dread as a cheap ploy, treating it with utter contempt. Savage, on the other hand, knows how to get the job done. By gradually moving the viewer’s eye through the many frames of Host, he produced suspense and anxiety out of thin air. In Dashcam, on the other hand, he throws jolts and jumps with glee, and by the game’s end, he understands that there is no such thing as going too far. Both styles are appropriate for their respective projects and demonstrate the filmmaker’s versatility.

“A fright scene has a rhythm,” Savage argues, referring to his unwavering commitment to terrifying the audience. “And I’m well-versed in all the tactics and clichés because I enjoy and study horror films.” “They are taken seriously by me.”

Is he done with computer screen horror now that he’s seen Host and Dashcam? “If there was a good idea,” he says, though it’s clear that he likes the idea of these two films being about a specific – and likely unrepeatable – period of time, adding, “I think these movies are polar opposites, and it’s fun to have done Host, which everyone seemed to get on board with, and then Dashcam, which has been a bit more divisive.”

To return to the director’s own words on Dashcam’s political potential, it’s all designed to be viewed as a “raucous movie you watch with a crowd.” “It’s an intoxicated movie,” he continues, warming to the idea. The host was the movie you watched alone in your bedsheets at home. [Dashcam] is my raunchy, yell-at-the-screen movie.” Go experience this blood-soaked, mad-as-a-hatter nightmare for yourself. You won’t be able to believe your eyes or ears.